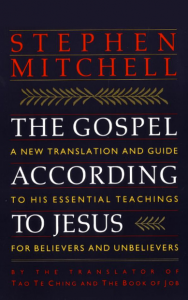

The Gospel According to Jesus

A New Translation and Guide to his Essential Teaching for Believers and Unbelievers

HarperCollins 1991

The Gospel According to Jesus is a dazzling new presentation of the life and teachings of Jesus by the eminent scholar and translator Stephen Mitchell. In this book, Mr. Mitchell does for the Gospels what he did for the Tao Te Ching: he uncovers in a great spiritual classic a depth, clarity, and radiance which have until now been obscured.

At the center of the book is a new translation, from the Greek, of what might be called the Essential Gospel. Following the example of Thomas Jefferson’s The Jefferson Bible, and using the best of modern scholarship, Mr. Mitchell has retained only the authentic sayings and doings of Jesus, and has omitted the passages added by the early church. What is left is an immensely provocative and moving image of Jesus as a real person and as a great spiritual teacher, an image that will challenge and delight readers of any religion or of no religion.

The Essential Gospel is preceded by a long meditation on Jesus’ life and teachings, and is followed by Mr. Mitchell’s detailed commentary on the text, which draws on his own Judeo-Zen background and on illuminating parallels from the Buddhist, Hindu, Taoist, Sufi, and Jewish traditions.

Excerpts

from the INTRODUCTION

I.

One of the icons on the walls of my study is a picture of Thomas Jefferson, an inexpensive reproduction of the portrait by Rembrandt Peale. The great man looks down over my desk, his longish, once-red hair almost completely gray now, a fur collar draped softly around his neck like a sleeping cat, his handsome features poised in an expression of serenity, amusement, and concern. I honor his serenity and understand his concern. And I like to think that his amusement—the hint of a smile, the left eyebrow raised a fraction of an inch—comes from finding himself placed in the company not of politicians but of saints.

For among the other icons on my walls are the beautiful, Jewish, halo-free face of Jesus by Rembrandt from the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin; a portrait of that other greatest of Jewish teachers, Spinoza; a Ming dynasty watercolor of a delighted bird-watching Taoist who could easily be Lao-tzu himself; a photograph, glowing with love, of the modern Indian sage Ramana Maharshi; and underneath it, surrounded by dried rose petals, a small Burmese statue of the Buddha, perched on a three-foot-tall packing crate stenciled with CHUE LUNG SOY SAUCE, 22 LBS.

Because Jefferson was our great champion of religious freedom, he was attacked as a rabid atheist by the bigots of his day. But he was a deeply religious man, and he spent a good deal of time thinking about Jesus of Nazareth. During the evening hours of one winter month late in his first term as president, after the public business had been put to rest, he began to compile a version of the Gospels that would include only what he considered the authentic accounts and sayings of Jesus. These he snipped out of his King James Bible and pasted onto the pages of a blank book, in more-or-less chronological order. He took up the project again in 1816, when he was seventy-three, eight years after the end of his second term, pasting in the Greek text as well, along with Latin and French translations, in parallel columns. The “wee little book,” which he entitled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, remained in his family until 1904, when it was published by order of the Fifty-seventh Congress and a copy given to each member of the House and Senate.

What is wrong with the old Gospels that made Jefferson want to compile a new one? He didn’t talk about this in public, but in his private correspondence he was very frank:

The whole history of these books [the Gospels] is so defective and doubtful that it seems vain to attempt minute enquiry into it: and such tricks have been played with their text, and with the texts of other books relating to them, that we have a right, from that cause, to entertain much doubt what parts of them are genuine. In the New Testament there is internal evidence that parts of it have proceeded from an extraordinary man; and that other parts are of the fabric of very inferior minds. It is as easy to separate those parts, as to pick out diamonds from dunghills. (To John Adams, January 24, 1814)

We must reduce our volume to the simple Evangelists; select, even from them, the very words only of Jesus, paring off the amphibologisms into which they have been led by forgetting often, or not understanding, what had fallen from him, by giving their own misconceptions as his dicta, and expressing unintelligibly for others what they had not understood themselves. There will be found remaining the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man. (To John Adams, October 12, 1813)

Jefferson’s robust honesty is always a delight, and never more so than in the Adams correspondence. The two venerable ex-presidents, who had been allies during the Revolution, then bitter political enemies, and who were now, in their seventies, reconciled and mellow correspondents, with an interest in philosophy and religion that almost equaled their fascination with politics ówhat a pleasure it is to overhear them discussing the Gospels sensibly, in terms that would have infuriated the narrow-minded Christians of their day. But Jefferson, too, called himself a Christian. “To the corruptions of Christianity,” he wrote, “I am, indeed, opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian in the only sense in which he wanted anyone to be: sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other.” It is precisely because of his love for Jesus that he had such contempt for the “tricks” that were played with the Gospel texts.

“Tricks” may seem like a harsh word to use about some of the Evangelists’ methods. But Jefferson was morally shocked to realize that the words of Jesus had been added to, deleted, altered, and otherwise tampered with as the Gospels were put together. He might have been more lenient if he were writing today, not as a member of a tiny clear-sighted minority, but in an age when textual skepticism is, at last, widely recognized as a path to Jesus, even by devout Christians, even by the Catholic church. For all reputable scholars today acknowledge that the official Gospels were compiled, in Greek, many decades after Jesus’ death, by men who had never heard his teaching, and that a great deal of what the “Jesus” of the Gospels says originated not in Jesus’ own Aramaic words, which have been lost forever, but in the very different teachings of the early church. And if we often can’t be certain of what he said, we can be certain of what he didn’t say.

In this book I have followed Jefferson’s example. I have selected and translated, from Mark, Matthew, Luke, and (very sparingly) from John, only those passages that seem to me authentic accounts and sayings of Jesus. When there are three accounts of the same incident, I have relied primarily on Mark, the oldest and in certain ways the most trustworthy of the three Synoptic Gospels. I have also included all the teachings from Matthew and from Luke that seemed authentic. And I have eliminated every passage and, even within authentic passages, every verse or phrase that seemed like a later theological or polemical or legendary accretion.

Gospel means “good news.” While the Gospels according to Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John are to a large extent teachings about Jesus, I wanted to compile a Gospel that would be the teaching of Jesus: what he proclaimed about the presence of God: good news as old as the universe. I found, as Jefferson did, that when the accretions are recognized and stripped off, Jesus surprisingly, vividly appears in all his radiance. Like the man in Bunyan’s riddle, the more we throw away, the more we have. Or the process of selection can be compared to a diamond cutter giving shape to a magnificent rough stone, until its full, intrinsic brilliance is revealed. Jefferson, of course, was working without any of the precision tools of modern scholarship, as if trying to shape a diamond with an axe. But he knew what a diamond looked like.

The scholarship of the past seventy-five years is an indispensable help in distinguishing the authentic Jesus from the inauthentic. No good scholar, for example, would call the Christmas stories anything but legends, or the accounts of Jesus’ trial anything but polemical fiction. And even about the sayings of Jesus, scholars show a remarkable degree of consensus.

In selecting passages from the Gospels, I have always taken seriously the strictly scholarly criteria. But there are no scholarly criteria for spiritual value. Ultimately my decisions were based on what Jefferson called “internal evidence”: the evidence provided by the words themselves. The authentic passages are marked by “sublime ideas of the Supreme Being, aphorisms and precepts of the purest morality and benevolence…, humility, innocence, and simplicity of manners…, with an eloquence and persuasiveness which have not been surpassed.” As Jesus said, the more we become sons (or daughters) of God, the more we become like God — generous, compassionate, impartial, serene. It is easy to recognize these qualities in the authentic sayings. They are Jesus’ signature.

To put it another way: when I use the word authentic, I don’t mean that a saying or incident can be proved to originate from the historical Jesus of Nazareth. There are no such proofs; there are only probabilities. And any selection is, by its nature, tentative. I may have included passages which, though filled with Jesus’ spirit, were actually created by an editor, or I may have excluded passages whose light I haven’t been able to see. But much of the internal evidence of seems to me beyond doubt. When we read the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son, or the saying about becoming like children if we wish to enter the kingdom of God, or the passages in the Sermon on the Mount that teach us to be like the lilies of the field and to love our enemies, “so that you may be sons of your Father in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the wicked and on the good, and sends rain to the righteous and to the unrighteous,” we know we are in the presence of the truth. If it wasn’t Jesus who said these things, it was (as in the old joke about Shakespeare) someone else by the same name. Here, in the essential sayings, we have words coming from the depths of the human heart, spoken from the most intimate experience of God’s compassion: words that can shine into a Muslim’s or a Buddhist’s or a Jew’s heart just as powerfully as into a Christian’s. Whoever spoke these words was one of the great world teachers, perhaps the greatest poet among them, and a brother to all the awakened ones. The words are as genuine as words can be. They are the touchstone of everything else about Jesus.

For me, then, Jesus’ words are authentic when scholarship indicates that they probably or possibly originated from him and when at the same time they speak with the voice that I hear in the essential sayings. This may seem like circular reasoning. But it isn’t reasoning at all; it is a mode of listening.

No careful reader of the Gospels can fail to be struck by the difference between the largeheartedness of such passages and the bitter, badgering tone of some of the passages added by the early church. It is not only the polemical element in the Gospels, the belief in devils, the flashy miracles, and the resurrection itself that readers like Jefferson, Tolstoy, and Gandhi have felt are unworthy of Jesus, but most of all, the direct antitheses to the authentic teaching that were put into “Jesus'” mouth, doctrines and attitudes so offensive that they “have caused good men to reject the whole in disgust.” Jesus teaches us, in his sayings and by his actions, not to judge (in the sense of not to condemn), but to keep our hearts open to all people; the later “Jesus” is the archetypal judge, who will float down terribly on the clouds for the world’s final rewards and condemnations.

Jesus cautions against anger and teaches the love of enemies; “Jesus” calls his enemies “children of the Devil” and attacks them with the utmost vituperation and contempt. Jesus talks of God as a loving father, even to the wicked; “Jesus” preaches a god who will cast the disobedient into everlasting flames. Jesus includes all people when he calls God “your Father in heaven”; “Jesus” says “my Father in heaven.” Jesus teaches that all those who make peace, and all those who love their enemies, are sons of God; “Jesus” refers to himself as “the Son of God.” Jesus isn’t interested in defining who he is (except for one passing reference to himself as a prophet); “Jesus” talks on and on about himself. Jesus teaches God’s absolute forgiveness; “Jesus” utters the horrifying statement that “whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit never has forgiveness but is guilty of an eternal sin.” The epitome of this narrowhearted, sectarian consciousness is a saying which a second-century Christian scribe put into the mouth of the resurrected Savior at the end of Mark: “Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved, but whoever doesn’t believe will be damned.” No wonder Jefferson said, with barely contained indignation,

Among the sayings and discourses imputed to him by his biographers, I find many passages of fine imagination, correct morality, and of the most lovely benevolence; and others again of so much ignorance, so much absurdity, so much untruth, charlatanism, and imposture, as to pronounce it impossible that such contradictions should have proceeded from the same being. (To William Short, April 13, 1820)

Once the sectarian passages are left out, we can recognize that Jesus speaks in harmony with the supreme teachings of all the great religions: the Upanishads, the Tao Te Ching, the Buddhist sutras, the Zen and Sufi and Hasidic Masters. I don’t mean that all these teachings say exactly the same thing. There are many different resonances, emphases, skillful means. But when words arise from the deepest kind of spiritual experience, from a heart pure of doctrines and beliefs, they transcend religious boundaries, and can speak to all people, male and female, bond and free, Greek and Jew.

The eighteenth-century Japanese Zen poet Ryokan, who was a true embodiment of Jesus’ advice to become like a child, said it like this:

In all ten directions of the universe,

there is only one truth.

When we see clearly, the great teachings are the same.

What can ever be lost? What can be attained?

If we attain something, it was there from the beginning of time.

If we lose something, it is hiding somewhere near us.

Look: this ball in my pocket:

can you see how priceless it is?

II.

What is the gospel according to Jesus? Simply this: that the love we all long for in our innermost heart is already present, beyond longing. Most of us can remember a time (it may have been just a moment) when we felt that everything in the world was exactly as it should be. Or we can think of a joy (it happened when we were children, perhaps, or the first time we fell in love) so vast that it was no longer inside us, but we were inside it. What we intuited then, and what we later thought was too good to be true, isn’t an illusion. It is real. It is realer than the real, more intimate than anything we can see or touch, “unreachable,” as the Upanishads say, “yet nearer than breath, than heartbeat.” The more deeply we receive it, the more real it becomes.

Like all the great spiritual Masters, Jesus taught one thing only: presence. Ultimate reality, the luminous, compassionate intelligence of the universe, is not somewhere else, in some heaven light-years away. It didn’t manifest itself any more fully to Abraham or Moses than to us, nor will it be any more present to some Messiah at the far end of time. It is always right here, right now. That is what the Bible means when it says that God’s true name isI am.

There is such a thing as nostalgia for the future. Both Judaism and Christianity ache with it. It is a vision of the Golden Age, the days of perpetual summer in a world of straw-eating lions and roses without thorns, when human life will be foolproof, and fulfilled in an endlessly prolonged finale of delight. I don’t mean to make fun of the messianic vision. In many ways it is admirable, and it has inspired political and religious leaders from Isaiah to Martin Luther King. But it is a kind of benign insanity. And if we take it seriously enough, if we live it twenty-four hours a day, we will spend all our time working in anticipation, and will never enter the Sabbath of the heart. How moving and at the same time how ridiculous is the story of the Hasidic rabbi who, every morning, as soon as he woke up, would rush out his front door to see if the Messiah had arrived.(Another Hasidic story, about a more mature stage of this consciousness, takes place at the Passover seder. The rabbi tells his chief disciple to go outside and see if the Messiah has come. “But Rabbi, if the Messiah came, wouldn’t you know it in here?” the disciple says, pointing to his heart. “Ah,” says the rabbi, pointing to his own heart, “but in here, the Messiah has already come.”) Who among the now-middle-aged doesn’t remember the fervor of the Sixties, when young people believed that love could transform the world? “You may say I’m a dreamer,” John Lennon sang, “but I’m not the only one.” The messianic dream of the future may be humanity’s sweetest dream. But it is a dream nevertheless, as long as there is a separation between inside and outside, as long as we don’t transform ourselves. And Jesus, like the Buddha, was a man who had awakened from all dreams.

When Jesus talked about the kingdom of God, he was not prophesying about some easy, danger-free perfection that will someday appear. He was talking about a state of being, a way of living at ease among the joys and sorrows of our world. It is possible, he said, to be as simple and beautiful as the birds of the sky or the lilies of the field, who are always within the eternal Now. This state of being is not something alien or mystical. We don’t need to earn it. It is already ours. Most of us lose it as we grow up and become self-conscious, but it doesn’t disappear forever; it is always there to be reclaimed, though we have to search hard in order to find it. The rich especially have a hard time reentering this state of being; they are so possessed by their possessions, so entrenched in their social power, that it is almost impossible for them to let go. Not that it is easy for any of us. But if we need reminding, we can always sit at the feet of our young children. They, because they haven’t yet developed a firm sense of past and future, accept the infinite abundance of the present with all their hearts, in complete trust. Entering the kingdom of God means feeling, as if we were floating in the womb of the universe, that we are being taken care of, always, at every moment.

All spiritual Masters, in all the great religious traditions, have come to experience the present as the only reality. The Gospel passages in which “Jesus” speaks of a kingdom of God in the future can’t be authentic, unless Jesus was a split personality, and could turn on and off two different consciousnesses as if they were hot- and cold-water faucets. And it is easy to understand how these passages would have been inserted into the Gospel by disciples, or disciples of disciples, who hadn’t understood his teaching. Passages about the kingdom of God as coming in the future are a dime a dozen in the prophets, in the Jewish apocalyptic writings of the first centuries B.C.E., in Paul and the early church. They are filled with passionate hope, with a desire for universal justice, and also, as Nietzsche so correctly insisted, with a festering resentment against “them” (the powerful, the ungodly). But they arise from ideas, not from an experience of the state of being that Jesus called the kingdom of God.

The Jewish Bible doesn’t talk much about this state; it is more interested in what Moses said at the bottom of the mountain than in what he saw at the top. But there are exceptions. The most dramatic is the Voice from the Whirlwind in the Book of Job, which I have examined at length elsewhere. Another famous passage occurs at the beginning of Genesis: God completes the work of creation by entering the Sabbath mind, the mind of absolute, joyous serenity; contemplates the whole universe and says, “Behold, it is very good.”

The kingdom of God is not something that will happen, because it isn’t something thatcan happen. It can’t appear in a world or a nation; it is a condition that has no plural, but only infinite singulars. Jesus spoke of people “entering” it, said that children were already inside it, told one particularly ardent scribe that he, the scribe, was not “far from” it. If only we stop looking forward and backward, he said, we will be able to devote ourselves to seeking the kingdom of God, which is right beneath our feet, right under our noses; and when we find it, food, clothing, and other necessities are given to us as well, as they are to the birds and the lilies. Where else but here and now can we find the grace-bestowing, inexhaustible presence of God? In its light, all our hopes and fears flitter away like ghosts. It is like a treasure buried in a field; it is like a pearl of great price; it is like coming home. When we find it, we find ourselves, rich beyond all dreams, and we realize that we can afford to lose everything else in the world, even (if we must) someone we love more dearly than life itself.

The portrait of Jesus that emerges from the authentic passages in the Gospels is of a man who has emptied himself of desires, doctrines, rules—all the mental claptrap and spiritual baggage that separate us from true life—and has been filled with the vivid reality of the Unnamable. Because he has let go of the merely personal, he is no one, he is everyone. Because he allows God through the personal, his personality is like a magnetic field. Those who are drawn to him have a hunger for the real; the closer they approach, the more they can feel the purity of his heart.

What is purity of heart? If we compare God to sunlight, we can say that the heart is like a window. Cravings, aversions, fixed judgments, concepts, beliefs—all forms of selfishness or self-protection—are, when we cling to them, like dirt on the windowpane. The thicker the dirt, the more opaque the window. When there is no dirt, the window is by its own nature perfectly transparent, and the light can stream through it without hindrance.

Or we can compare a pure heart to a spacious, light-filled room. People or possibilities open the door and walk in; the room will receive them, however many they are, for as long as they want to stay, and will let them leave when they want to. Whereas a corrupted heart is like a room cluttered with valuable possessions, in which the owner sits behind a locked door, with a loaded gun.

One last comparison, from the viewpoint of spiritual practice. To grow in purity of heart is to grow like a tree. The tree doesn’t try to wrench its roots out of the earth and plant itself in the sky, nor does it reach its leaves downward into the dirt. It needs both ground and sunlight, and knows the direction of each. Only because it digs into the dark earth with its roots is it able to hold its leaves out to receive the sunlight.

For every teacher who lives in this way, the word of God has become flesh, and there is no longer a separation between body and spirit. Everything he or she does proclaims the kingdom of God. (A visitor once said of the eighteenth-century Hasidic rabbi Dov Baer, “I didn’t travel to Mezritch to hear him teach, but to watch him tie his shoelaces.”)

People can feel Jesus’ radiance whether or not he is teaching or healing; they can feel it in proportion to their own openness. There is a deep sense of peace in his presence, and a sense of respect for him that far exceeds what they have felt for any other human being. Even his silence is eloquent. He is immediately recognizable by the quality of his aliveness, by his disinterestedness and compassion. He is like a mirror for us all, showing us who we essentially are.

The image of the Master:

one glimpse

and we are in love.

He enjoys eating and drinking, he likes to be around women and children; he laughs easily, and his wit can cut like a surgeon’s scalpel. His trust in God is as natural as breathing, and in God’s presence he is himself fully present. In his bearing, in his very language, he reflects God’s deep love for everything that is earthly: for the sick and the despised, the morally admirable and the morally repugnant, for weeds as well as flowers, lions as well as lambs. He teaches that just as the sun gives light to both wicked and good, and the rain brings nourishment to both righteous and unrighteous, God’s compassion embraces all people. There are no pre-conditions for it, nothing we need to do first, nothing we have to believe. When we are ready to receive it, it is there. And the more we live in its presence, the more effortlessly it flows through us, until we find that we no longer need external rules or Bibles or Messiahs.

For this teaching which I give you today is not hidden from you, and is not far away. It is not in heaven, for you to say, “Who will go up to heaven and bring it down for us, so that we can hear it and do it?” Nor is it beyond the sea, for you to say, “Who will cross the sea and bring it back for us, so that we can hear it and do it?” But the teaching is very near you: it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can do it.

He wants to tell everyone about the great freedom: how it feels when we continually surrender to the moment and allow our hearts to become pure, not clinging to past or future, not judging or being judged. In each person he meets he can see the image of God in which they were created. They are all perfect, when he looks at them from the Sabbath mind. From another, complementary, viewpoint, they are all imperfect, even the most righteous of them, even he himself, because nothing is perfect but the One. He understands that being human means making mistakes. When we acknowledge this in all humility, without wanting anything else, we can forgive ourselves, and we can begin correcting our mistakes. And once we forgive ourselves, we can forgive anyone.

He has no ideas to teach, only presence. He has no doctrines to give, only the gift of his own freedom.

Tolerant like the sky,

all-pervading like sunlight,

firm like a mountain,

supple like a branch in the wind,

he has no destination in view

and makes use of anything

life happens to bring his way.Nothing is impossible for him.

Because he has let go,

he can care for the people’s welfare

as a mother cares for her child.

Reviews

Stephen Mitchell restores the lovely, fiery, utterly brave and unique voice of Jesus to us — and the result is a real gift, a blessing, even (one dares think) a moment of grace.

–Robert Coles, Commonweal

Stephen Mitchell’s The Gospel According to Jesus is bound to be an extremely controversial book. Properly read, which is unlikely, the book would give Christendom a well-deserved spiritual earthquake. The book is a masterpiece of immense power and permanence.

–Jim Harrison

Even more than his meticulous scholarship, his farsighted commentary and elegant translation, the greatest contribution Mitchell has to make is his generosity of spirit. The Gospel According to Jesus is a bottomless text, so large-hearted that it can cause one to gasp with wonder and relief.

–Gail Caldwell, Boston Sunday Globe

If there is such a thing as spiritual entertainment, that is exactly what Mitchell has given us.

–Joseph Coates, Chicago Tribune Book World

Countless authors have written about Jesus, but few have plucked such a resonant chord with readers . . . Unlike some studies of Jesus that become bogged down in bloodless academic disputation, The Gospel According to Jesus is a work of heart.

–Los Angeles Times Magazine

Mitchell has culled through the synoptic writings and given us brisk and accurate renderings, paired with his fascinating reflections on them and some apt comparisons to other philosophers, Zen masters, visionaries, and poets. This approach succeeds brilliantly. Jesus, or at least Mitchell’s attractive portrait of him, leaps into life and will fire the interest of believers and nonbelievers alike.

–Harvey Cox, Tikkun

Thank God for Stephen Mitchell. His latest book, The Gospel According to Jesus, is excellent reading for those who prefer being pulled from preoccupation with self to the poetic and profound. The introduction alone offers enough fresh and disturbing ideas to be worth the price of the book… The center of the book is a new translation from the Greek of the sayings of Jesus and commentary on the same. By using the best of modern scholarship, Mitchell strips the gospel to its essence, omitting all passages that were added by the early church. As a result the “good news” is once again news. In the hands of this sculptor of words, the reflections on the text are masterpieces.

–Mary Lou Kownacki, Commonweal

Mitchell’s translations of the Tao Te Ching and The Book of Job are widely regarded as masterpieces; this book is even more valuable. We live in a civilization based on a twisted compromise of Jesus’ teachings, and this very credible account of what Jesus may have actually said is a small but potent antidote.

–Michael Ventura, L. A. Weekly

Very provocative and very thoughtful — a remarkable book.

–Studs Terkel, WSMT

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.