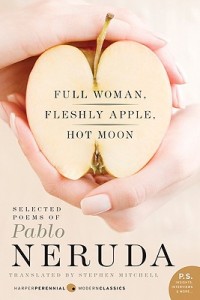

Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon

Selected Poems of Pablo Neruda

HarperCollins 1997

Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon is a new presentation of the poetry of Pablo Neruda, the most widely read and loved poet of the twentieth century. Out of the great profusion of Neruda’s poetry, Stephen Mitchell has selected forty-nine poems and brought them to life for a whole new generation of readers.

Excerpts

Pablo Neruda’s poetry is vast in many ways. There are several thousand pages of it, to begin with, very uneven in quality but stunning in its sheer profusion. Neruda couldn’t help writing poems, he wrote as naturally as he breathed, wrote with the unthinking, exuberant abundance of Nature herself. He makes most other great modern poets seem pinched, restrained, perfectionistic. Compared with him, even Whitman had writer’s block.

Making a selection from this abundance was like standing in some treasure cave from The Thousand and One Nights: coffers and urns overbrimming with jewels lay all around me, but my companion genie said I was only allowed to fill my own pockets. So I made no effort to be representative, to take an equal number of diamonds, pearls, emeralds, sapphires, rings, massive necklaces, filagree bracelets, pre-Columbian animal figurines of pure gold, platinum large-breasted goddesses with ruby nipples. I just took what I loved most. When my pockets were full, I left.

I had to leave behind many of Neruda’s greatest poems, because they weren’t my favorites: the passionate youthful hymns to sex of Twenty Poems of Love, the dark, lonely, outraged, restless brilliance of Residence on Earth, the encyclopedic hymn to the Americas that is Canto General, with its masterpiece “The Heights of Macchu Picchu.” As great as some of these poems obviously are, I am not often drawn to reread them.

The poetry of Neruda’s that I love best, that I do reread with an always-renewed pleasure, is the poetry of his ripeness, beginning with the first book of Elemental Odes, published when he was fifty years old, and ending with Full Powers, published when he was fifty-eight, eleven years before his death. These are the poems of a happy man, deeply fulfilled in his sexuality, at home in the world, in love with life and its infinite particular forms, overflowing with the joy of language. They are largehearted, generous poems, resonant with a humor that is rare in modern poetry, in any poetry. The sometimes showy surrealism of the earlier poems has mellowed into a constant, delicious skating on the edge of nonsense.

If “love calls us to the things of this world,” in Richard Wilbur’s memorable phrase, Neruda is one of the most loving poets who has ever written. We may be put off by the doctrinaire and self-dramatizing comradeliness of the more political poems, but there is a deeper sense of genuine communion that speaks through all his mature work. His sources of inspiration are unlimited. He turns his attention to an elephant or a pair of socks or time or an artichoke or an atom or a star or a bar of soap, and immediately it comes to life, it becomes the center of the universe, linked in an often astonishing series of metaphors to anything and everything else in the interconnected web of beings. The con-nections are so ceaseless, so surprising, that we may find ourselves racing to keep up with the fecundity of his imagination, gasping for breath at the brilliance and rightness of it all.

I enter these poems with delight and leave them with exhilaration, grateful for the vividness with which they let me see the world through the eyes of a fabulously intelligent child. “Behold, I make all things new.” Neruda would have hated to have me quote Revelation about him. But the spirit of poetry, whether or not we call it holy, does make all things new. And Neruda, who gathers so many of the things of this world into his large embrace, brings us closer to the loving, humorous, compassionate source of all these things, since, with all his impassioned love for language, he is a poet who can say:

I utter and I am

and across the boundary of words,

without speaking, I approach silence.

✷

ODE TO THE ONION

Onion,

luminous flask,

your beauty formed

petal by petal,

crystal scales expanded you

and in the secrecy of the dark earth

your belly grew round with dew.

Under the earth

the miracle

happened

and when your clumsy

green stem appeared,

and your leaves were born

like swords

in the garden,

the earth heaped up her power

showing your naked transparency,

and as the remote sea

in lifting the breasts of Aphrodite

duplicated the magnolia,

so did the earth

make you,

onion,

clear as a planet,

and destined

to shine,

constant constellation,

round rose of water,

upon

the table

of the poor.

Generously

you undo

your globe of freshness

in the fervent consummation

of the cooking pot,

and the crystal shred

in the flaming heat of the oil

is transformed into a curled golden feather.

Then, too, I will recall how fertile

is your influence on the love of the salad,

and it seems that the sky contributes

by giving you the shape of hailstones

to celebrate your chopped brightness

on the hemispheres of a tomato.

But within reach

of the hands of the common people,

sprinkled with oil,

dusted

with a bit of salt,

you kill the hunger

of the day-laborer on his hard path.

Star of the poor,

fairy godmother

wrapped

in delicate

paper, you rise from the ground

eternal, whole, pure

like an astral seed,

and when the kitchen knife

cuts you, there arises

the only tear

without sorrow.

You make us cry without hurting us.

I have praised everything that exists,

but to me, onion, you are

more beautiful than a bird

of dazzling feathers,

you are to my eyes

a heavenly globe, a platinum goblet,

an unmoving dance

of the snowy anemone

and the fragrance of the earth lives

in your crystalline nature.

ODE TO MY SOCKS

Maru Mori brought me

a pair

of socks

which she knitted with her own

sheepherder hands,

two socks as soft

as rabbits.

I slipped my feet

into them

as if they were

two

cases

knitted

with threads of

twilight

and the pelt of sheep.

Outrageous socks,

my feet became

two fish

made of wool,

two long sharks

of ultramarine blue

crossed

by one golden hair,

two gigantic blackbirds,

two cannons:

my feet

were honored

in this way

by

these

heavenly

socks.

They were

so beautiful

that for the first time

my feet seemed to me

unacceptable

like two decrepit

firemen, firemen

unworthy

of that embroidered

fire,

of those luminous

socks.

Nevertheless,

I resisted

the sharp temptation

to save them

as schoolboys

keep

fireflies,

as scholars

collect

sacred documents,

I resisted

the wild impulse

to put them

in a golden

cage

and each day give them

birdseed

and chunks of pink melon.

Like explorers

in the jungle

who hand over the rare

green deer

to the roasting spit

and eat it

with remorse,

I stretched out

my feet

and pulled on

the

magnificent

socks

and

then my shoes.

And the moral of my ode

is this:

beauty is twice

beauty

and what is good is doubly

good

when it’s a matter of two

woolen socks

in winter.

KEEPING QUIET

Now we will count to twelve

and we will all keep still.

This one time upon the earth,

let’s not speak any language,

let’s stop for one second,

and not move our arms so much.

It would be a delicious moment,

without hurry, without locomotives,

all of us would be together

in a sudden uneasiness.

The fishermen in the cold sea

would do no harm to the whales

and the peasant gathering salt

would look at his torn hands.

Those who prepare green wars,

wars of gas, wars of fire,

victories without survivors,

would put on clean clothing

and would walk alongside their brothers

in the shade, without doing a thing.

What I want shouldn’t be confused

with final inactivity:

life alone is what matters,

I want nothing to do with death.

If we weren’t unanimous

about keeping our lives so much in motion,

if we could do nothing for once,

perhaps a great silence would

interrupt this sadness,

this never understanding ourselves

and threatening ourselves with death,

perhaps the earth is teaching us

when everything seems to be dead

and then everything is alive.

Now I will count to twelve

and you keep quiet and I’ll go.

BESTIARY

If only I could speak with birds,

with oysters and with small lizards,

with the foxes of Selva Oscura,

with representative penguins,

if the sheep would listen to me,

the languorous, woolly dogs,

the huge carriage-horses, if only

I could talk things over with the cats,

if the chickens could understand me!

I have never felt the urge to speak

with aristocratic animals:

I am not at all interested

in the world view of the wasps

or the opinions of thoroughbred horses:

so what, if they go on flying

or winning ribbons at the track!

I want to speak with the flies,

with the bitch who has just given birth,

to have a long chat with the snakes.

When my feet were able to walk

through triple nights, now past,

I followed the nocturnal dogs,

those squalid, incessant travelers

who trot around town in silence

in their great rush to nowhere,

and I followed them for hours,

they were quite suspicious of me,

those poor foolish dogs,

they lost the opportunity

of telling me their sorrows,

of running with grief and a tail

through the avenues of the ghosts.

I was always very curious

about the erotic rabbit:

who provokes it and whispers

into its genital ears?

It never stops procreating

and takes no notice of Saint Francis,

doesn’t listen to nonsense:

the rabbit keeps on humping

with its inexhaustible mechanism.

I’d like to speak with the rabbit,

I love its sexy customs.

The spiders have always been slandered

in the idiotic pages

of exasperating simplifiers

who take the fly’s point of view,

who describe them as devouring,

carnal, unfaithful, lascivious.

For me, that reputation

discredits just those who concocted it:

the spider is an engineer,

a divine maker of watches,

for one fly more or less

let the imbeciles detest them,

I want to have a talk with the spider,

I want her to weave me a star.

The fleas interest me so much

that I let them bite me for hours,

they are perfect, ancient, Sanskritic,

they are inexorable machines.

They don’t bite in order to eat,

they bite in order to jump,

they’re the globe’s champion highjumpers,

the smoothest and most profound

acrobats in the circus:

let them gallop across my skin,

let them reveal their emotions

and amuse themselves with my blood,

just let me be introduced to them,

I want to know them from up close,

I want to know what I can count on.

With the ruminants I haven’t been able

to achieve an intimate friendship:

I myself am a ruminant, I can’t see

why they don’t understand me.

I’ll have to study this theme

grazing with cows and oxen,

making plans with the bulls.

Somehow I will come to know

so many intestinal things

hidden inside my body

like the most clandestine passions.

What do pigs think of the dawn?

They don’t sing but they carry it

with their large pink bodies,

with their little hard hoofs.

The pigs carry the dawn.

The birds eat up the night.

And in the morning the world

is deserted: the spiders sleep,

the humans, the dogs, the wind sleeps,

the pigs grunt, and day breaks.

I want to have a talk with the pigs.

Sweet, loud, harsh-voiced frogs,

I have always wanted to be

a frog, I have loved the pools

and the leaves, thin as filaments,

the green world of the watercress

with the frogs, queens of the sky.

The serenade of the frog

rises in my dream and excites it,

rises like a climbing vine

to the balconies of my childhood,

to the budding nipples of my cousin,

to the astronomic jasmine

of the black night of the South,

and now so much time has passed,

don’t ask me about the sky:

I feel that I haven’t yet learned

the harsh-voiced idiom of the frogs.

If this is so, how am I a poet?

What do I know of the multiplied

geography of the night?

In this world that rushes and grows calm

I want more communications,

other languages, other signs,

to be intimate with this world.

Everyone has remained content

with the sinister presentations

of rapid capitalists

and systematic women.

I want to speak with many things

and I won’t leave this planet

without knowing what I came to find,

without resolving this matter,

and people are not enough,

I have to go much farther

and I have to get much closer.

And so, gentlemen, I’m going

to have a talk with a horse,

let the poetess excuse me

and let the professor pardon me,

all week I’ll be busy,

I have to constantly listen.

What was the name of that cat?

ODE TO IRONING

Poetry is white:

it comes from the water covered with drops,

it wrinkles and piles up,

the skin of this planet must be stretched,

the sea of its whiteness must be ironed,

and the hands move and move,

the holy surfaces are smoothed out,

and that is how things are made:

hands make the world each day,

fire becomes one with steel,

linen, canvas, and cotton arrive

from the combat of the laundries,

and out of light a dove is born:

chastity returns from the foam.